In the shallow waters off Japan, hermit crabs are engaged in a complex social game that would make any chess master proud. These seemingly simple creatures maintain detailed mental records of their neighbors, tracking who’s tough, who’s weak, and crucially – who just lost their primary weapon in battle.

Memory Under the Sea

Most of us think of memory as a uniquely human trait, or at least something limited to “smart” animals like dolphins, elephants, or primates. But groundbreaking research by Japanese scientist Chiaki Yasuda is revealing that even hermit crabs possess surprisingly sophisticated memory systems that would put some computer databases to shame.

The hermit crab Pagurus middendorffii lives in a world where males constantly compete for the right to guard females before mating. It’s a high-stakes environment where the wrong fight can mean wasted energy, serious injury, or missed reproductive opportunities. In this competitive landscape, being smart about who to fight – and who to avoid – can be the difference between genetic success and failure.

Nature’s Bouncers

Think of subordinate hermit crabs as nature’s bouncers, constantly making split-second decisions about whether to engage potential troublemakers. Through painful experience, these crabs learn to identify the tough guys in their neighborhood – the dominant males who consistently win fights and aren’t worth challenging.

This recognition system works brilliantly as an energy-saving strategy. Why waste time and risk injury fighting someone you’ve already lost to? Better to recognize them from a distance and find easier targets elsewhere. It’s a logical system that many animals use to avoid costly conflicts.

But hermit crabs face a unique problem that makes their world more unpredictable than most.

The Disappearing Weapon Problem

Unlike animals with permanent weapons – think deer antlers or rhino horns – hermit crabs carry weapons that can vanish in seconds. Their primary fighting tool is a large claw called a major cheliped, which they use for grabbing, pinching, and intimidating opponents. But when danger strikes, these crabs can deliberately drop their claw through a process called autotomy, sacrificing their weapon to save their life.

Imagine if a heavyweight boxer could suddenly lose their dominant hand in the middle of a match. That’s essentially what happens when a hermit crab autotomizes its major claw. The former champion becomes, quite literally, disarmed and vulnerable.

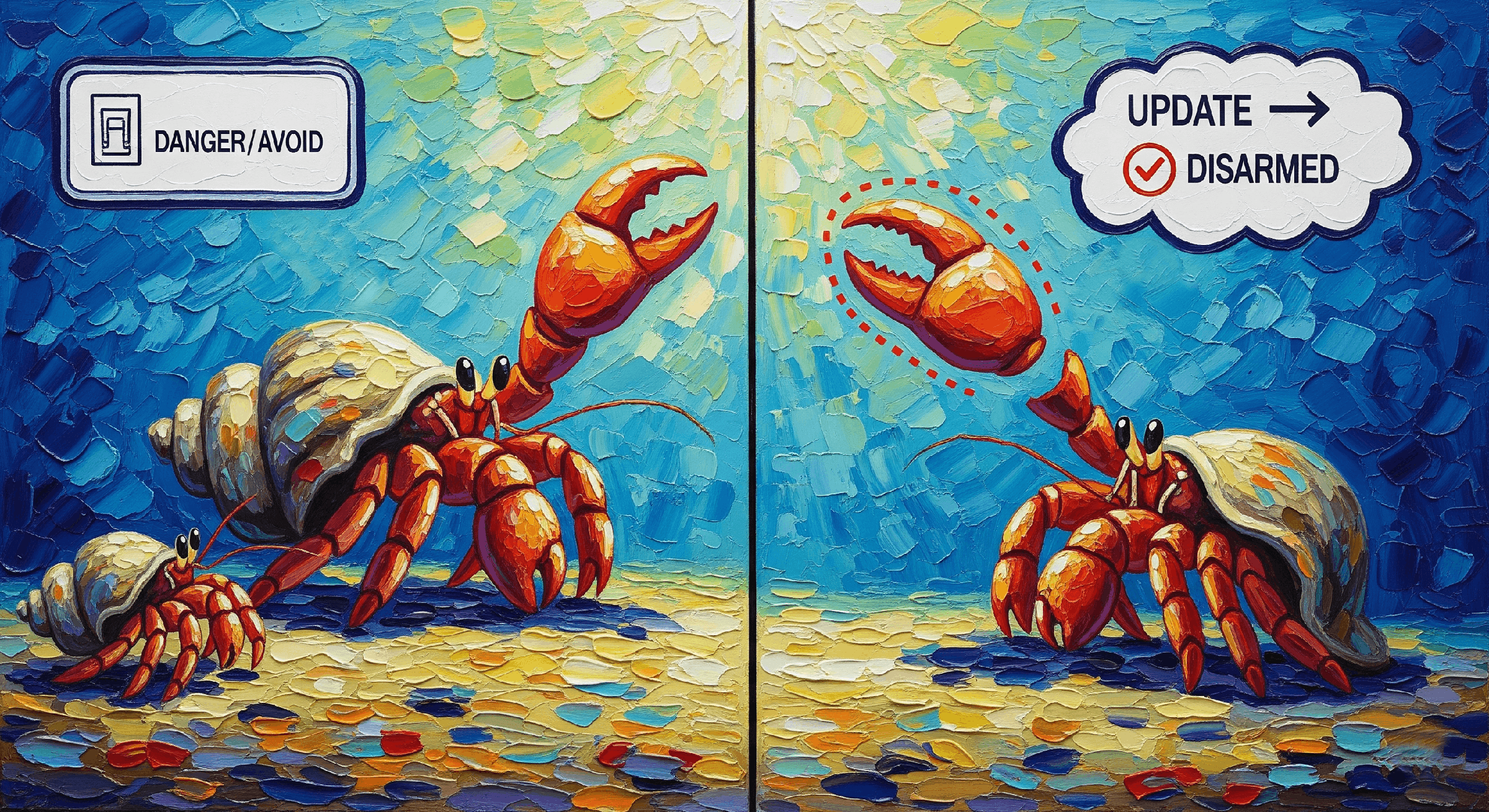

This creates a fascinating puzzle: if you’re a subordinate crab who has learned to avoid a particular dominant opponent, what do you do when you encounter that same opponent after they’ve lost their main weapon? Do you stick to your old avoidance pattern, or do you reassess the situation?

A Laboratory Drama

To solve this puzzle, researcher Yasuda created a controlled drama in his laboratory, complete with protagonists, conflicts, and plot twists. The experimental setup was elegantly simple: hermit crab males competing over access to females, with carefully orchestrated encounters that would reveal the hidden workings of crustacean cognition.

Act One established the social hierarchy. Subordinate males were introduced to dominant males guarding females, and predictably, the subordinates lost every encounter. This wasn’t just about establishing winners and losers – it was about creating memories. Each subordinate crab now had a mental file: “This particular individual beat me. Avoid future confrontations.”

During the intermission, Yasuda introduced his experimental manipulation. Some of the previously victorious dominants were induced to autotomize their major claw, transforming from well-armed champions into weaponless has-beens. Others remained intact as controls.

Act Two would reveal whether hermit crabs could rewrite their mental files in real-time.

The Plot Twist

When the curtain rose on the second act, something unexpected happened. The subordinate crabs didn’t simply apply their old avoidance patterns. Instead, they seemed to perform rapid battlefield assessments, weighing their opponent’s identity against their current condition.

Subordinates who encountered familiar but now-weaponless dominants suddenly became aggressive, launching attacks they had never dared attempt before. These weren’t random acts of violence – they were calculated risks based on updated intelligence about their opponent’s fighting capacity.

The numbers tell a compelling story. Against familiar dominants who still possessed their weapons, subordinates rarely escalated conflicts, maintaining their learned avoidance patterns. But against familiar dominants who had lost their claws, subordinates escalated fights much more frequently, engaged in longer battles, and achieved dramatically better outcomes – winning 25% of encounters and drawing another 50%.

Crustacean Intelligence in Action

What makes this remarkable isn’t just that hermit crabs can remember individual opponents – it’s that they can simultaneously track multiple attributes of those opponents and update their assessments when circumstances change. This requires a form of flexible thinking that scientists call “information updating.”

Consider what’s happening in a subordinate crab’s mind during these encounters. The crab must recognize the specific individual (“I know this opponent”), recall their previous interaction (“This individual beat me before”), assess their current condition (“But they’ve lost their primary weapon”), calculate new odds of success (“My chances are much better now”), and decide on a course of action (“I’ll risk a fight”).

This cognitive sequence involves memory retrieval, situational assessment, probabilistic reasoning, and strategic decision-making – a surprisingly sophisticated mental process for an animal with a brain smaller than a pinhead.

The Cognitive Revolution in Invertebrates: What Hermit Crabs Tell Us About Animal Intelligence

The implications of this research extend far beyond the world of hermit crabs. For decades, scientists have debated the cognitive abilities of invertebrates, often assuming that creatures with simple nervous systems were limited to basic, inflexible responses to their environment.

But Yasuda’s hermit crabs are demonstrating something much more nuanced: the ability to maintain complex social databases that can be updated in real-time based on changing circumstances. They’re not just following simple rules like “avoid this individual” – they’re maintaining detailed profiles that include both identity and current status.

This kind of cognitive flexibility was once thought to be the exclusive domain of vertebrates with more complex brains. The discovery that hermit crabs can engage in information updating suggests that sophisticated mental abilities may be more widespread in the animal kingdom than previously imagined.

From Observation to Understanding: The Mysteries Behind Hermit Crab Cognitive Abilities

While this research provides fascinating insights into hermit crab cognition, it also raises intriguing questions about the mechanisms underlying these abilities. How do subordinate crabs detect that a familiar dominant has lost its weapon? Are they relying on visual cues, chemical signals, behavioral changes, or some combination of factors?

The research also opens broader questions about the evolution of intelligence. If hermit crabs can update their social assessments, what other invertebrates might possess similar capabilities? How did these cognitive abilities evolve, and what advantages do they provide in natural environments?

A New Perspective: What Hermit Crabs Teach Us About Intelligence in Nature

This study challenges us to reconsider our assumptions about intelligence in nature. The hermit crabs in Yasuda’s laboratory demonstrated a form of social intelligence that many humans would find familiar: the ability to maintain relationships with known individuals while adapting to changing circumstances.

In human terms, it’s like remembering that your usually dominant colleague has been having a rough time lately and might be more open to negotiation than usual. The hermit crabs are essentially doing the same thing – maintaining social awareness while staying flexible enough to capitalize on new opportunities.

The next time you encounter a hermit crab in a tide pool, take a moment to appreciate the complex mental world hidden within that borrowed shell. Behind those tiny eyes lies a brain capable of maintaining detailed social records, performing real-time risk assessments, and making strategic decisions that would impress any military strategist.

In the competitive world of hermit crabs, intelligence isn’t just an academic curiosity – it’s a survival tool that can determine reproductive success and evolutionary fitness. These small crustaceans remind us that in nature, size doesn’t always correlate with smarts, and some of the most impressive cognitive abilities can be found in the most unexpected places.

Click here

Leave a Reply